History

Our History

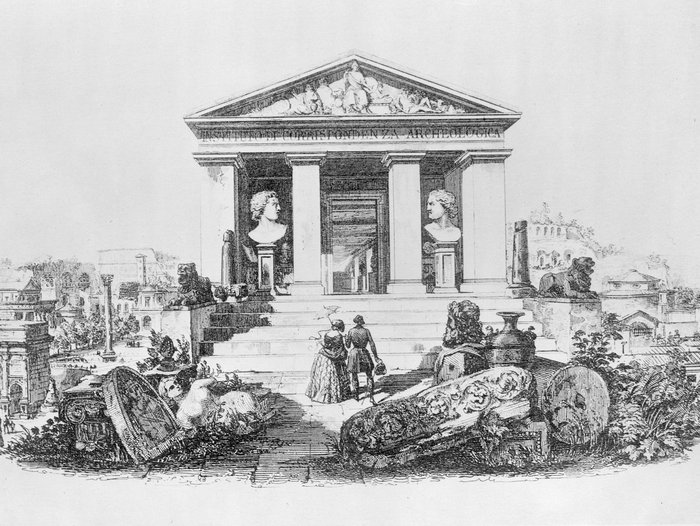

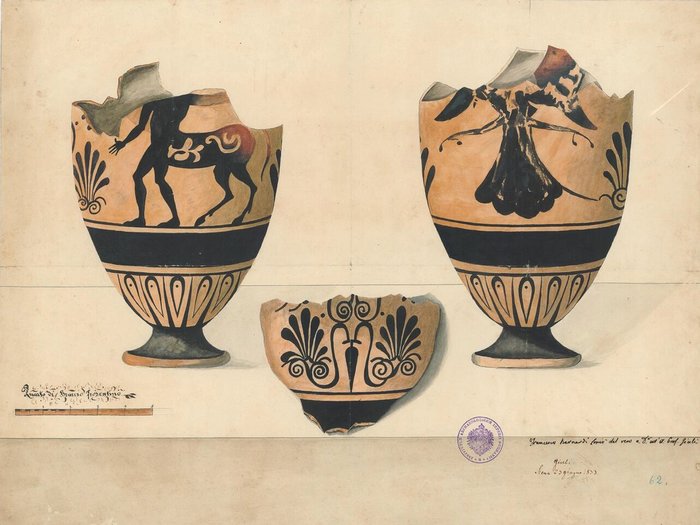

In 1829, a group of archaeologists and artists founded the Instituto di Corrispondenza Archeologica in Rome. The implicated, high-ranking personalities were organised in an array of national sections (one Italian, one English, one French, and one Prussian respectively in Rome, London, Paris, and Berlin). This to begin with private association began its activities by collecting and regularly publishing the ever-increasing number of Italy's archaeological discoveries. Soon, however, systematic investigations were launched, whether relating to the Greek vases recovered from Etruscan tombs or to the paintings of the tombs themselves. These investigations as also the studies on the ancient sculpture kept in Rome's museums, and those on 'the eternal city's' topography and architecture, or the abundant corpus of epigraphic finds were published in large monographs. The Instituto thus had set out to collect and publish all archaeological discoveries in the field of classical antiquity.

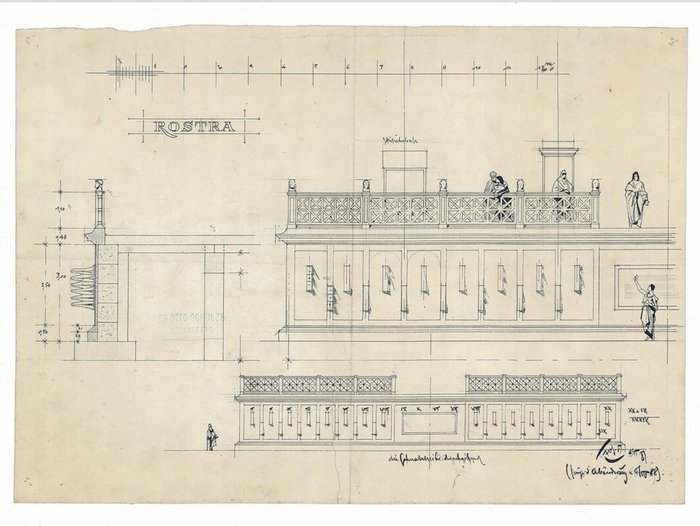

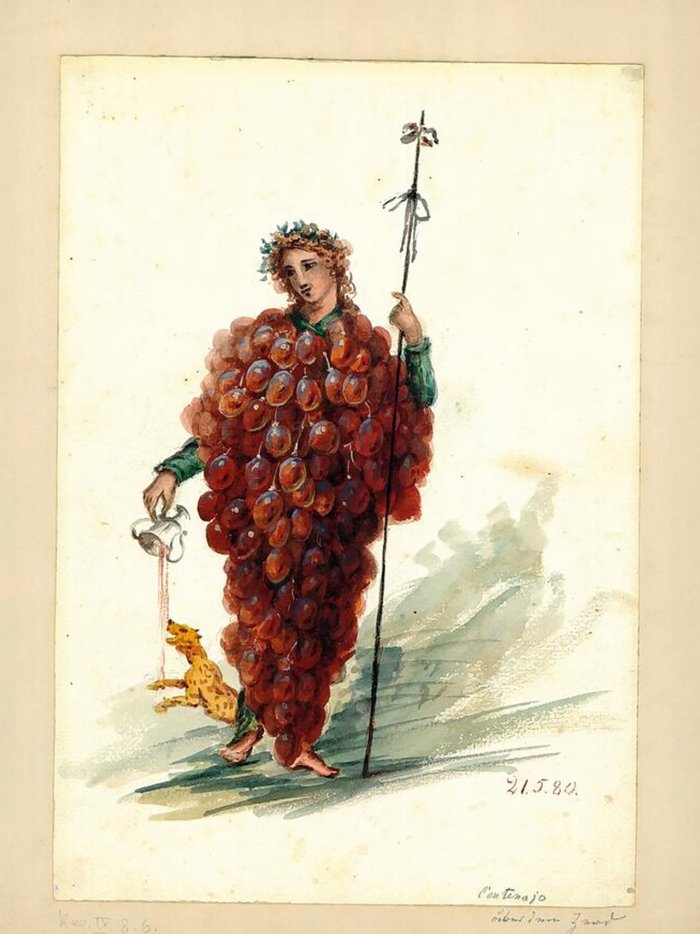

Added to this came the research accompanying the great Italian excavations, as the ones in Pompeii during the second half of the 19th century. Hosts of separate investigations dedicated to Rome and Latium's outstanding monuments like the Hellenistic temples or the Column of Marcus Aurelius, but also large catalogue works such as the still compelling scholarly guidebooks to the museums in Rome are just but some of the testimonies countersigning the institute's successful scientific work. The institute also played an essential role in the planning and implementation of large compilations like the so-called Roman Sarkophag-Corpus, founded in 1869/70 on behalf of the central administration of the Imperial German Archaeological Institute, or the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL) founded by Theodor Mommsen in 1863. WWI came as a major turning point after Italy joined the hostilities in 1915. The library was packed into boxes and shipped to Castel Sant'Angelo. The buildings in the southern part of the Capitoline Hill occupied until then by the German Empire, including the institute building of the DAI, were fully evacuated. The question as to whether the German research institutions in Italy were to be returned to German administration or transferred to Italian ownership became a matter of controversial debate. But in 1920 it was finally agreed to return the holdings to Germany, as endorsed by prominent personalities like the philosopher, historian, and politician Benedetto Croce who played an active role leading to this decision. The agreement stated a special condition that the library was to stay in Rome and remain accessible to Germans and Italians alike. After more than nine years of closure, the library was thus finally reopened at the end of 1924. The same applied for the institute as a whole which moved into its new premises in the protestant parish house in Via Sardegna, where it could resume the intense research activity it had pursued prior to the war. The dictatorship under National Socialism and the following outbreak of WWII also left their marks on the Roman institute: Jewish colleagues were denied access to the library as from 1938, and some new research projects like that concerning the Langobards partly remain incomprehensible without the interference from Third Reich ideology.

Even though the institute remained temporarily open until the end of 1943, Führer directives ordered the evacuation of scientific inventories of German libraries in Italy after Rome's occupation by German troops in September of that same year. The books of the archaeological institute were thus put away into 1500 boxes at the beginning of 1944 and transferred to the salt mines at Alt-Aussee near Salzburg.

However, the relocation was not to last for very long, because after pressure from international colleagues in Rome, the library holdings were confiscated by the American military in Austria in 1945 and soon shipped back to Rome. Library operations on a limited scale thus became possible again witin the premises of the protestant parish house already by the end of 1947. Fortunately, the library transfers hardly had been marked by any loss. The reopened library came under the auspices of the Associazione Internazionale di Archeologia Classica (AIAC) which remained in charge until 1953. After initial intensive discussions concerning its permanent international status, thawing political conditions in the early 1950s together with voiced support from numerous, both Italian and international colleagues finally led to the library's restitution to the state of the Federal Republic of Germany. In a treaty between the Western Allies represented by France, Great Britain, and the USA on the one hand, and Italy and the Federal Republic of Germany on the other, the permanent location of the library was yet again stipulated to remain in Rome and its accessibility guaranteed for all researchers, no matter their origin.

The 1960s and 1970s on the one hand were marked by a re-evaluation of Roman imperial art. One of the essential reasons for this were the rich holdings of the photo library. On the other hand, this period corresponds to the beginning of large-scale field projects and architectural research in Sicily, Lower Italy, and North Africa, which since then have be extended to Sardinia, Northern Italy, and the Adriatic Sea and now cover a chronological span reaching from the late 2nd millennium BC to the early Middle Ages.