Alfred Brueckner (1861–1936): On special leave for the Kerameikos excavation

Born in Magdeburg on 7 September 1861, as the son of the merchant Eduard Brueckner, Alfred graduated from the state high school at the former Monastery of Our Lady in his hometown in 1880. He was then immediately enlisted for two years of military service and posted to Strasbourg in 1881–1882. After his military service, he took up the study of archaeology under Adolf Michaelis in Strasbourg. Four years later, in 1886, he obtained his doctorate with a dissertation entitled »Ornament und Form attischer Grabstelen«

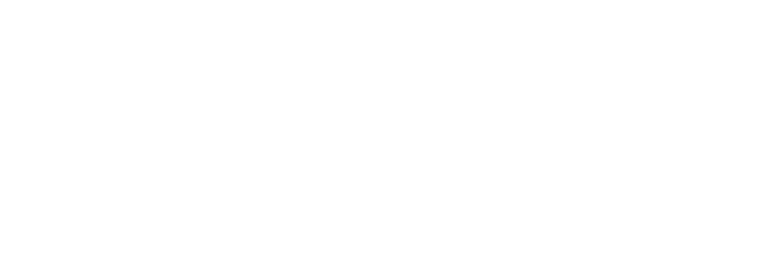

Fig. 1: Alfred Brueckner in the old Kerameikos Museum © Archive of the Headquarters Berlin, private papers Alfred Brueckner// N.N.

In order to make a living, he applied for a teaching position at the Prinz Heinrich-Gymnasium, a newly founded public elite boys’ school in Berlin-Schöneberg under the patronage of Kaiser Wilhelm II. However, he initially deferred taking up his position, having received a two-year travel grant from the DAI. This was to be Alfred Brueckner’s first visit to Greece and Athens (fig. 2), marking the beginning of a connection that would shape his life. As part of the grant, he participated in Heinrich Schliemann’s (1822–1890) excavations at Troy in 1890.

Fig. 2 Alfred Brueckner during his trip as travel grant holder, in the cemetery of Thebes © Archive of the DAI Berlin, A. Brueckner Bequest// N.N.

1891–1906

Returning home in 1891, Brueckner duly took up his teaching position. He remained in the school’s service without interruption until 1924, and had to apply for special leave to participate in every excavation campaign until his retirement. He taught Latin, Greek, history and geography. He earned an annual salary of 3,300 marks, with an additional 660 marks granted for accommodation. In 1924, he was succeeded at the same school by another pupil of Adolf Michaelis, the Jewish archaeologist Otto Rubensohn (1867–1964). Alongside its excellent tuition in the Classical languages, the school offered its pupils regular trips to Rome. It also provided teaching in Hebrew and Jewish religious studies.

In 1891, shortly after taking up his teaching post, Brueckner returned to Athens, where he joined Erich Pernice (1864–1945) and the architect Georg Kawerau (1856–1909) on an excavation led by Valerios Stais (1857–1923) on what is now Psaromilingou Street. An excavation report was published in the Athenische Mitteilungen in 1893. At the request of Sophia Schliemann, Brueckner also took on the editing of her late husband’s autobiography, which was published in 1892. It was during this period that he earned his nickname, ›Pater Desiderius‹, for successfully responding to countless enquiries and requests from his colleagues in Berlin.

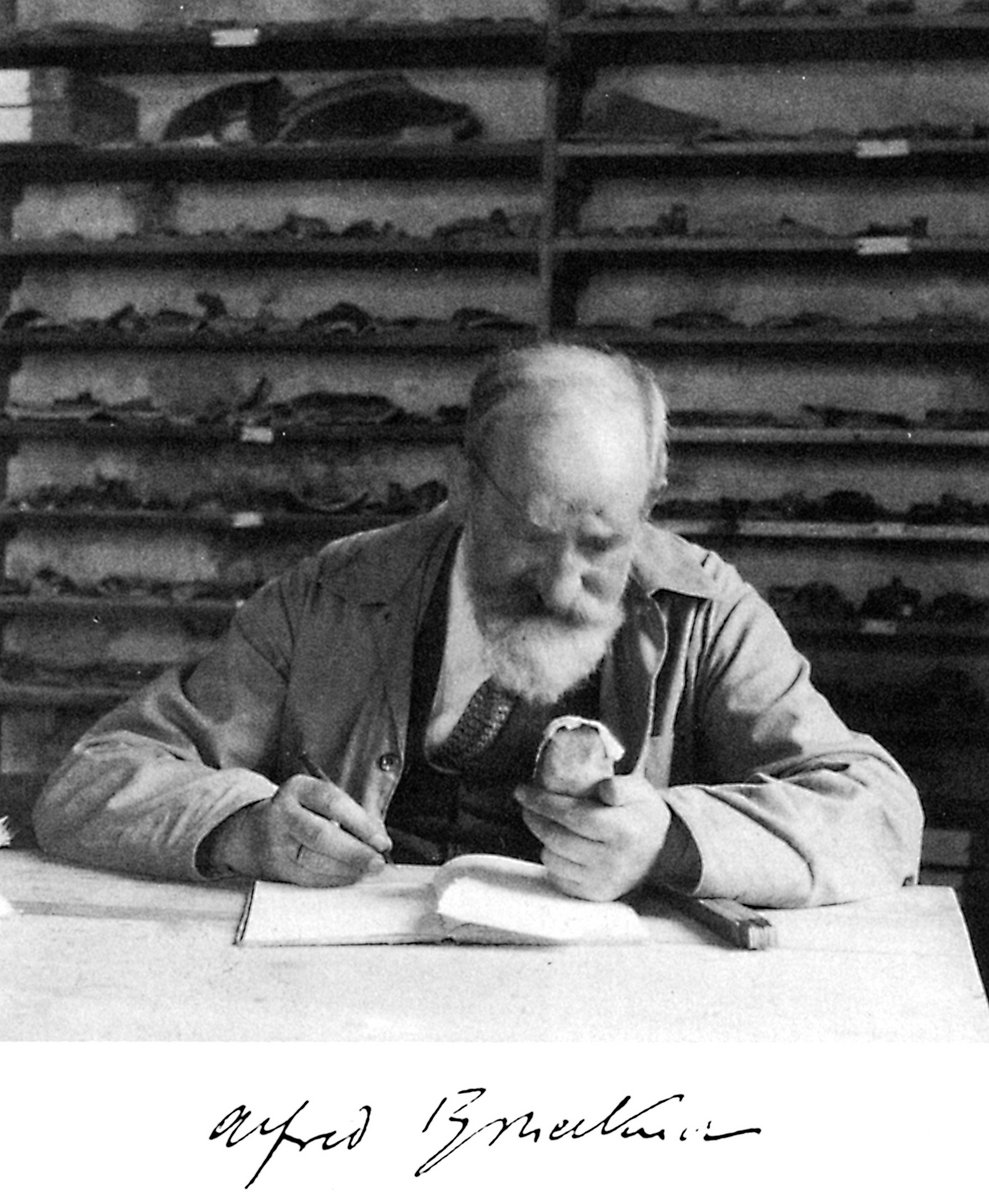

In 1893, Brueckner returned to Troy, where the excavations were now being led by Wilhelm Dörpfeld (1853–1940). Drawings of pottery were among his tasks there. His contribution is duly acknowledged in Dörpfeld’s publication »Troja und Ilion: Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen in den vorhistorischen und historischen Schichten von Ilion 1870–1894« (Athens 1902) (fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Troy 1893. Excavation team riding camels, with baggage. Left: Alfred Brueckner © Wuppertal City Archive, W. Dörpfeld Bequest// N.N.

In 1897, aged 36, Brueckner married Hedwig Minssen. Their son, Peter, was born shortly afterwards. In the years following World War I, Hedwig accompanied Alfred on his trips to Athens, and she supported him in his work on the Kerameikos until the end. Hedwig’s role in the excavations was not confined to that of a ›back-up‹. She was paid for the photographs, drawings, and restoration work she did on finds.

Brueckner was never an employee of the DAI Athens. He was simply provided with funds for excavations during campaigns. Therefore, he was not automatically entitled to live at the DAI while in Athens. In many years, however, he did request and receive a permit to do so (e.g. in 1909). In other years, and particularly in 1930, his last year in the Kerameikos, he was forced to seek other solutions. During this final year, he and his wife lived at number 18 Alexandra’s Avenue.

1907–1916

Between 1907–1910 Brueckner returned to Athens, first to work on the »Corpus der griechischen Grabreliefs«, a project of the Vienna Academy of Sciences. Following the death of Alexander Conze (1831–1914), he continued and completed the fourth volume of the corpus. As part of this project, he made copies of hundreds of inscriptions. He also deployed his skills in draughtsmanship once more, creating, for instance, watercolours of marble monuments that preserved traces of colour (fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Kerameikos, Inv. Co 397 remnants of paint on the kioniskos of Apollodorus, son of Timaeus of Pallene, 1910 © DAI Athens, Archive of the Kerameikos Excavation// Watercolour by Alfred Brueckner

Second, in 1907, he conducted his first excavations on the Kerameikos site, commissioned by the Archaeological Service – and with sponsorship from the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences, a stipend from the Eduard Gerhard Foundation (which he shared with Richard Delbrueck, Saale-Zeitung, July 20, 1907, Supplement 1, 1) and the Archaeological Service of Athens. As a result, Panagiotis Kavvadias (1850–1928), then Ephor-General (Secretary) of the Archaeological Society in Athens (1895–1909 and 1912–1920), was severely criticised in the Greek press for using Greek funds to enable foreign scholars to excavate in the Kerameikos. Kavvadias was relieved of his office for this reason (among others) in 1909. Nevertheless, Bruckner’s work resulted in the monograph »Der Friedhof am Eridanos«, which he dedicated to Kavvadias as a mark of their friendship. To this day, it remains a crucial documentation of the excavations and finds in the Kerameikos, and particularly of the Classical grave precincts. It was ultimately because of Brueckner’s work and personal connections that the excavation permit came to be transferred to the DAI in 1913, as Georg Karo (1872–1963), then director of the DAI Athens testified in his letter to Brueckner dated 25 July 1913: »The glorious gift that has fallen into our lap thanks to you!« – referring to the Kerameikos excavation. Brueckner led the first campaigns of the Kerameikos excavation on behalf of the DAI Athens from 1913 to 1915. He also commissioned the construction of the first museum in the Kerameikos in 1913 to ensure the safekeeping of the finds (fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Kerameikos, First Museum built at the Kerameikos in 1914 © DAI Athens, Archive of the Kerameikos Excavation// N.N.

Brueckner’s work in the Kerameikos was characterised by close observation, his openness to cooperation and his abundant background knowledge, which enabled him to classify the finds from his campaigns. The excavation of the sanctuary of the Tritopatores was another of his accomplishments. He also initiated the first systematic cooperation between anthropologists and archaeologists in Athens in 1910, when he and Marinos Geroulanos (1867–1960) excavated the Heracleot precinct on the Street of the Tombs together. Brueckner was honoured for his accomplishments in 1915, receiving the Officer’s Cross of the Royal Greek Order of the Redeemer (Τάγμα του Σωτήρος). In 1916, he was elected as an honorary member of the Archaeological Society in Athens. The fourth campaign of the Kerameikos excavation was continued by Hubert Knackfuss (1866–1948), but had to be suspended upon Greece’s entry into World War I in November 1916.

Between 1924 and 1927, Brueckner embarked on a project with the linen manufacturer and Privy Councillor Dr. Oskar Mey (1867–1942) of Bäumenheim in Bavaria, that aimed to produce a detailed topographical map of the Troad. Brueckner received 5000 marks for this project from the Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft (Aid Association of German Science), and was granted a travel bursary. However, the Turkish government, for strategic reasons (relating to the Dardanelles), refused to issue the required permits. Instead, Brueckner compiled extensive collections of material (inscriptions etc.) in the Troad, into which he incorporated material from the bequest of Frank R. Calvert (1928–1908).

1926–1930

Alfred Brueckner was reinstated as director of the excavations in the Kerameikos at the request of the Greek authorities in 1926. The DAI appointed the architect Hubert Knackfuss to assist him again. A photo from this period shows Hedwig Brueckner with the excavation team in the Kerameikos (fig. 6).

Fig. 6 Participants in the Kerameikos excavation 1927-1930. Seated in the foreground, Hedwig Brueckner née Minssen. Standing, left to right: Anton H. Hess, Karl Kübler, Hubert Knackfuss, Alfred Brueckner, Major Fritz Wirth and Willy Zschietschmann © DAI Athens, KER 1031// N.N.

After carrying out the necessary clearance work, Brueckner resumed the interrupted systematic excavations along the Kerameikos road, and began to excavate the Pompeion. On 7 April 1930, the discovery of a fragment of the inscription from the Tomb of the Lacedaemonians (IG II 11678) confirmed that this tomb complex in front of the Dipylon, parts of which Brueckner had found back in 1914, was identifiable as the grave of the Spartans who had fallen as allies of the Thirty Tyrants in a battle between their supporters and the democrats during the Athenian Civil War in 403 BC – as mentioned in Xenophon, Hellenica 2,4,31–33 and Lysias 2, 63. Both the inscription and Xenophon’s account name three individuals who fell in that battle – the polemarchs (generals) Chaeron and Thibrachus, and the Olympic victor Lacrates, who – like all Spartan Olympians – formed part of the Spartan king’s bodyguard in battle. This discovery of the inscription fragment marks one of those glorious moments in archaeology when, in one instant, a single find sheds light on an entire historical episode and adds to our knowledge in many ways. This sensational discovery brought affirmation and gratification to Brueckner (fig. 7).

Fig. 7 Kerameikos Inv. I 170. Fragment of the inscription from the Tomb of the Lacedaemonians © DAI Athens, KER 1986// H. Wagner

The find, however, triggered a wave of reactions, most of which Brueckner found bewildering and incomprehensible. Georg Karo, then in his second term as Director of the DAI Athens (1930–1936), appeared daily at the Kerameikos from that point until the end of the excavations in early June. Despite not being an excavating archaeologist, Karo proceeded to interfere in the excavation process. He also began soliciting hostile written testimony about Brueckner’s way of working and his personality. Among those to respond were Karl Kübler (on June 28, 1930), the restorer Kurt Lindig (1898–1957), and the art historian, Major (retd) Fritz Wirth. This concerted action was so effective that at the German Archaeological Institute’s Central Directorate meeting of mid-July 1930, the decision was made to bar Brueckner from the Kerameikos excavation with immediate effect. On 14 July 1930, Walter Wrede (1893–1990) trumpeted to Georg Karo, »The Dragon of the Eridanus is driven out […] Next, he will receive correction to his beer newspaper [meaning the excavation report]«. Brueckner approached Wrede, Gerhard Rodenwaldt, Karo, and Kübler for explanations and assistance – but was, of course, unsuccessful.

This predicament robbed Brueckner of his sleep and appetite, ultimately making him ill. His physical and mental health deteriorated considerably in his final years. He died in Berlin on 15 January 1936.

Not one of the German archaeologists who took over the Kerameikos excavation from Brueckner paid him tribute in any way. Brueckner’s contributions to the Kerameikos excavation were to be forgotten. Nevertheless, the DAI retains the excavation permit for the Kerameikos, a thorough inventory of the Classical grave precincts along the Cemetery Road, detailed diaries, and thousands of photographs of the terrain and of finds, all incorporated into the DAI Athens photographic archive. One German obituary did appear, by Karl Anton Neugebauer (1886–1945), previously curator of the Berlin Museums, who had been forced to abandon his career as a classical archaeologist in 1933 because his wife, Erna Jacobi, was Jewish. For the Greeks, the task of celebrating Brueckner fell to Marinos Kalligas. He praised him as »εἰδικώτατος« and »χρησιμότατος«. And while the brief and businesslike obituary by David Moore Robinson confines itself entirely to scientific work, it does at least do justice to some of Brueckner’s accomplishments.

Works cited and further reading:

Karl Anton Neugebauer, Nachruf auf Alfred Brueckner, Archäologischer Anzeiger 1936, 234–238

Μαρίνος Καλλιγάς, Prakt 1936 [1937] 1 f.

David Moore Robinson, AJA 41, 1937, 118 f.

Rudolf H. W. Stichel, Alfred Brueckner, in: Reinhard Lullies – Wolfgang Schiering (eds.), Archäologenbildnisse. Porträts und Kurzbiographien von Klassischen Archäologen deutscher Sprache (Mainz 1988) 144 f.