Preliminary investigation of Sukur Cultural Landscape in northeast Nigeria

In danger and endangered: Preliminary investigation of Sukur Cultural Landscape in northeast Nigeria

Abstract

World Heritage Sites and areas are places with evidence of cultural heritage with Outstanding Univer- sal Values (OUVs) to people and the world at large. However, in the last 15 years, some of the listed world heritage sites are being threatened by many factors. These risks can either be natural and human-induced disasters. Human-induced disasters range from uranisation, construction, farming, deforestation, poaching, poor management, and conflict. In the northern part of Nigeria where this study has been carried out, armed conflict is the most prominent threat to the integrity of the only world heritage site inscribed in this region, Sukur World Heritage site. Using satellite imagery with a temporal resolution of four years starting from 2009 to 2021, the study found out that armed conflict threatens cultural heritage in a substantial way. This impact is mostly noticeable in the transformation from the traditional form of house architecture to a supposed contemporary form of ar- chitecture which invariably threatens the integrity of the heritage site.

Introduction

Archaeological and heritage sites are often prone to destruction from both natural and human-induced factors. Natural factors such as earthquakes, tsuna- mis, floods, and human-induced disasters such as climate change, urbanisation, farming, looting, war, and conflict pose serious threats to the survival of sites and monuments around the world (WHC 2007c). In developing countries however, the rate at which the integrity of sites is threatened particularly through con- flicts, illegal activities, terrorism, and development-led constructions has risen significantly in the last decade (Levin et al. 2019). According to UNESCO (2006), 43% of listed global World Heritage Sites in danger are in Africa, and most of them are now threatened. While humans, often, are completely helpless when natural disasters happen, most sites around the world have been victims of human-induced disasters especially cultural terrorism and armed banditry (Brosché et al. 2017; Frey & Steiner 2011).

Armed banditry and cultural terrorism in the northern part of Nigeria has led to the destruction of lives, properties, and cultural heritage sites in the last 15 years (Nwanegbo & Odigbo 2013; Gilbert 2014). One of the 36 states in Nigeria where armed banditry and terrorism have been rampant in the last decade is Adamawa State (Nwakaudu 2012). Adamawa State is home to Sukur Cultural Landscape (SCL), one of the two World Heritage Sites in Nigeria. SCL was inscribed into the World Heritage List in November 1999 owing to its cultural heritage, material culture and the naturaly terraced fields.

According to UNESCO (1999), its inscription was based on three criteria:

- iii. Sukur is an exceptional landscape that graphi- cally illustrates a form of land use that marks a crit- ical stage in human settlement and its relationship with its environment.

- The cultural landscape of Sukur has survived unchanged for many centuries and continues to do so at a period when this form of traditional hu- man settlement is under threat in many parts of the world.

- vi. The cultural landscape of Sukur is eloquent tes- timony to a strong and continuing spiritual and cultural tradition that has endured for many cen- turies.’

Archaeological excavations in the area have yielded iron-smelting furnaces, shafts, and bellows close to houses, pointing to a complex socioeconomic relationship that existed on the landscape (UNESCO/NCMM 1998).

Figure 1. House structure in Sukur with dome-shaped roof. © Akinbowale M. Akintayo// Akinbowale M. Akintayo

Over the centuries, SCL has survived a plethora of natural and human-induced disasters, and as such, has remained relatively un- changed (UNESCO 1999). One notable structure in Sukur is the hilltop settlement which has the Hidi (Chief) Palace at the centre, sacred symbols, and rit- ual sites which further attest to the spiritual culture in Sukur (UNESCO/NCMM 1998). As one moves down the hill, there are terraced fields on which residents plant crops and rear animals.

However, the activities of the Boko Haram sect have caused SCL to suffer devastating blows which has led to the destruction of lives, properties, and the envi- ronment since 2012 (Nwanegbo & Odigbo 2013; Gil- bert 2014; Anyadike 2013; Walker 2012). At Hidi’s Pal- ace, traditional stone buildings, paved walkways, cow

pens, granaries, ritual sites, and festival grounds were destroyed during the raid by the insurgents in Decem- ber 2014 (David & Sterner 2014). It is therefore imperative that an assessment of the state of conservation of this cultural landscape be carried out to evaluate its condition on the one hand, and to identify if there are threats posed to the survival of this heritage site. This is necessary because:

i.) The activities of Boko Haram in northern Nige- ria have led to the destruction of lives and properties and Madagali local government is one of the local governments that has witnessed insurgence of the sect.

ii.) Traditional human settlement patterns around the world are faced with both natural and human-induced disasters from urbanisation.

Previous research in Sukur has focused on iron smelting (Sassoon 1964), tourism development (Finanga & Husain 2013), ethnoarchaeology of Sukur (David 1998), challenges of safeguarding cultural heritage materials, sustainable development (Sterner 2010), historical ethnography of Sukur (David & Sterner 1995; 1996), and conservation management (Eboreime 2003). This paper examines the extent to which the cultural landscape of Sukur has changed in the wake of activities of the Boko Haram sect regarding build- ing and fencing architectures. The building architec- ture in Sukur, like in most parts of northern Nigeria, are rounded huts with mud dome roof type (Figure 1). The mud roof type is then protected with a thatched roof covering to serve as a waterproof layer to prevent the mud domes from disintegration when exposed to the elements.

Study Area

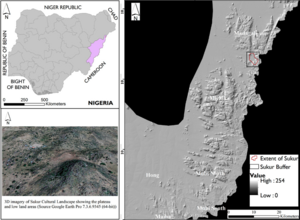

Sukur Cultural Landscape (N 10 44 260 E 13 34 190) is in Madagali Local Government Area of Adamawa State, Nigeria (Figure 2). According to Kinjir (2001), SCL is about 245 km from Yola, the Adamawa State capital, and 15 km from Gulak which is the headquar- ters of Madagali Local Government. Sukur Cultural Landscape – which consists of the Plateau and its adjoining lowland settlement – is the first World Heritage Site to be inscribed into the list in Africa (UNE- SCO 1999).

Situated along the Nigeria/Cameroon border at an elevation of 1,045 m, the ancient hilltop settlement was famous for iron smelting technology, flourishing trade and a strong political institution that dates to the sixteenth century CE.

Figure 2. Location of Sukur Cultural Landscape in Adamawa State of Nigeria. © Akinbowale M. Akintayo// Akinbowale M. Akintayo

The core of Sukur covers an area of about 764.40 hectares while Sukur buffer covers an area of about 1,178.10 hectares (UNESCO 1999).

Data acquisition and pre-processing

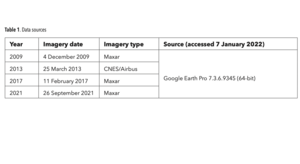

Sukur core (which in this context refers to the hill- top settlement) and Sukur buffer zone (adjoining and lowland areas) were digitised from the working document of the National Commission for Museums and Monuments in Nigeria to extract its area extent. This served as Area of Interest (AoI) employed for the study. Historical satellite imagery used in this study was accessed from Google Earth Pro 7.3.6.9345 (64- bit) interface using the time slider tool. 2009 was selected as the first year of study because of data availability and because it marks the tenth year of the inscription of SCL on the UNESCO World Heritage Site list. Subsequently, images taken at four-year in- tervals (2013, 2017 and 2021) spanning a period of

Table 1. Data Sources © Akinbowale M. Akintayo// Akinbowale M. Akintayo

12 years were analysed for the study. A grid system was used to divide the Area of Interest covering SCL into cells to get the required extent (Sukur buffer) of imagery for each year and imagery covering each grid cell was then saved as very high-resolution im- agery. Afterwards, a composite image for each of the years was then saved before being imported into the ArcGIS for further analysis.

Furthermore, Sukur Buffer and Sukur extent shapefiles were used as vector data files to clip the raster imagery for all the years. Then, the AoI was used as a vector data to clip 1.) the Digital Elevation Model – to provide a pictorial representation of the terrain of the area being studied (Figure 2) and 2.) the imageries for the years to provide the baseline area for the analysis. Furthermore, building footprints were superimposed on the imagery for all the years being studied. Finally, for all the images of each year, build ing footprints with aluminium roofing sheets that fall within the clipped extent of the AoI were digitised and counted.

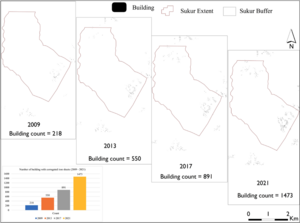

Spatial distribution of buildings with corrugated iron sheets in Sukur in 2009, 2013, 2017, and 2021. Inset: bar chart showing the distribution. © Akinbowale M. Akintayo// Akinbowale M. Akintayo

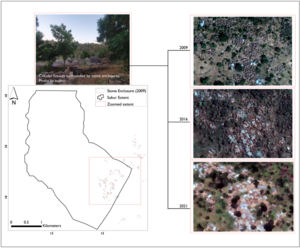

Distribution of stone enclosure fencing system in Sukur in 2009, 2016 and 2021 © Akinbowale M. Akintayo// Akinbowale M. Akintayo

Results and discussion

Aside from the bespoke roof architecture (Figure 1) which characterises the house roofing system in Sukur, the presence of stone enclosure fencing sys- tem round the huts is another feature that makes it unique (Figure 3).

The result of the analyses (Figure 4) showed that in 2009, 10 years after the inscription of SCL in the World Heritage Site list, most of the buildings were conventional round houses with thatched roof sys-

tem surrounded by stone enclosures as fencing sys- tems, while the number of buildings with aluminium roofing sheets was 218. However, in 2013, the num- ber of buildings with aluminium roofing sheets has increased to 550 (app. 152% increase). In another four years (2017), the number increased to 891 (app. 309% increase), and finally, in 2021 (12 years after), the number jumped to 1,473 (app. 576% increase) with very few stone enclosure fencing systems still vis- ible from satellite imagery.

One of the major factors attributed to the in- crease in the number of buildings with corrugated iron sheets (post-2014) is the scarcity of plant materi- als, the major material required for weaving thatchedroofs (UNESCO 2018). This is an aftermath of the at- tack by insurgents in December 2014. It was report- ed that about 173 houses were burned. This burning accordingly led to the destruction of thatched roofs and granary covers. Also, roofing logs on which corru- gated iron sheets are placed were destroyed with fire, thereby causing the roofs to collapse (David & Sterner 2014). During this attack, the Hidi Palace, the Palace Square, the Blacksmith Homestead, paved walkways, cow pens, granaries, threshing fields, ritual sites, and festival grounds were all affected by the activities of the insurgents (David & Sterner 2014; UNESCO 2016).

As all their crops were burned by the insurgents during the attack, they had to rebuild and make use of readily available roofing sheets which were part of the relief materials donated to the community after the attack by the insurgents. This has had a negative im- pact on the integrity of the landscape (David &Sterner 2014). Moreover, paved walkways which are an essen- tial part of the cultural landscape have been impacted negatively by erosion. This is due to the nature of the topography of the land. To reduce the rate of erosion, the community has been encouraged to engage in ac- tivities that could remediate the effect of erosion such as filling up areas affected by erosion with stones and rubble. Other factors responsible for the change in house architecture relates to conformity to contempo- rary trends of house structures, lifestyle change, pop- ulation pressure (Day et al. 2022). Satellite imagery of 2009 revealed the extent to which this fencing system was given a pride of place on the landscape. However, in 2016, the fencing system started collapsing and by 2021, there was a near-total collapse of most of these enclosures with exceptions in just a few places (Fig- ure 5).

As put by Feilden and Jokilehto (1998), the Man- agement Guidelines for World Cultural Heritage Sites posits that a site deserves delisting if both the site and its integrity are threatened by serious and specific dan- gers which are caused by either man or nature (Alberts and Hazen, 2010). Sukur is an agrarian community with most of the inhabitants engaging in farming as a form of livelihood, and field crops were also burned by these insurgents. The implication of this is that harvests were reduced, which in turn led to a scarcity of plant materials used for roof construction. Although the gov- ernment agency saddled with the responsibility of pre- serving the site is doing its best to preserve this site

given the resources available to it, much still needs to be done to protect this heritage site before cultural ter- rorism and climate change completely invalidate its in- tegrity and erase the memories of features which make up the heritage site.

Conclusion

World Heritage Sites around the world are often threat- ened by human activities. In most parts of Africa, these sites have been subjected to various menaces ranging from uncontrolled development-led constructions, attacks from armed bandits, and cultural terrorism. Sukur Cultural Landscape has been plagued by cultur- al terrorism resulting from armed banditry in the last 12 years. Most of the features which qualified the her- itage site for inscription on the World Heritage List are threatened by a chain of factors, starting with terrorism. Also, the destruction of paved walkways in Sukur has accelerated the rate of erosion, while the burning of crops and overgrazing have led to the scarcity of grass- es required to make thatched roofs. Therefore, tradi- tional forms of house architecture are changing from what they used to be to something alien to the envi- ronment, as corrugated iron sheets have replaced the thatched roof system which Sukur is known for. If the trend continues unchecked, it is just a matter of time before the heritage site loses the very essence of why it was inscribed.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Deutsche Archaeologische Institut (DAI) under the Global Archaeology, Sustainable Archaeology, and the Archaeology of Sustainability research fellowship. I am grateful to all authors whose works I consulted while preparing the manuscript.